Does House Rules really rule?

- cyborgcaveman

- Aug 26, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Nov 28, 2025

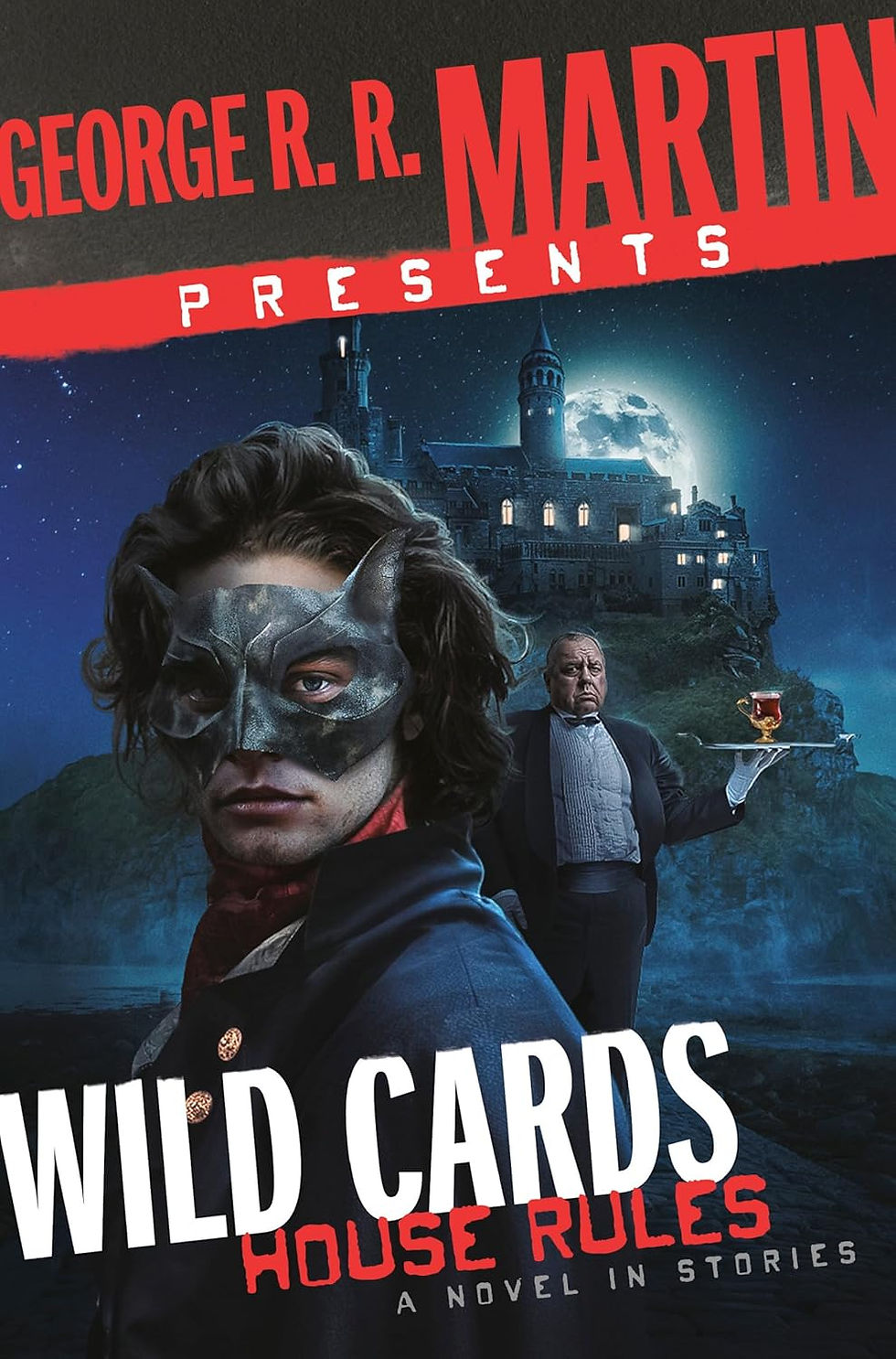

Wild Cards: House Rules

Edited by Georgie RR Martin and Melissa M. Snodgrass

If you don't know who the sucker is at the table, it's you. That bit of card playing wisdom seems a thematically appropriate enough place to begin this review, because after reading House Rules, the latest book from the Wild Cards series, I think the sucker might be me. If you'd like to skip the preamble and get to the actual review of House Rules, click here. If you want the bigger picture of the series and how House Rules fits into it, read on.

What is Wild Cards?

For those unfamiliar with Wild Cards, it is a long running series of books edited by George RR Martin, he of later Game of Thrones fame, and written by a who's who of sci-fi, including the late, great Roger Zelazny. The stories take place in a world which diverged from our own following the end of WWII. Human-like aliens decide to test a virus on the genetically identical inhabitants of Earth. The aliens called it the Enhancer, because it was originally meant to enhance their innate psionic powers. Humans called it the wild card, because of its highly unpredictable effects. Ninety of every hundred infected "draw the Black Queen" and die, often in horrific and violent ways; melting into goo, spontaneously combusting, ripped apart by their own mutating skeletal structure, and other showy forms of shuffling off the mortal coil. Of the ten survivors, nine become "jokers", twisted mutant freaks with deformed bodies or powers that manifest in uncontrollable or detrimental ways. One of every hundred infected become an "ace", blessed with beneficial powers that range from super strength to teleportation to laser beams to bringing inanimate objects to life or just about anything else you can imagine. The modes of death, joker mutations, and ace powers can all be as varied and unique as the personalities of those infected.

Everything in the WC universe evolves out of that premise. From 1946 onward, the heroes and villains of Wild Cards live in an alternate timeline to our own with key historical events changed by the presence of the virus. Stalin's joker status was concealed by burning his body. Gandhi was saved from assassination by an ace. Castro became an MLB pitching coach and never went on to rule Cuba. Between 1946 and now, that's a lot of history.

Going strong or going wrong?

First published in the 80s when grim and gritty superheroes were all the rage, Wild Cards was grimmer and grittier than most other exercises in deconstructing the super hero genre. The books eventually got to the point where it was so grimdark the by now mildly infamous ninth volume of the series, Jokertown Shuffle, turned off or alienated many of their own readers. I wasn't one of them. I appreciated the unflinching, transgressive grand guignol quality of Jokertown Shuffle, warts and all, and should probably review it one day just because that particular chapter of the saga was so polarizing, but I digress.

Point is, the series has gone through a variety of contributing authors and publishing houses, dying down then surging back to life every decade or so. However, perhaps in response to modern social mores, changing tides in popular fiction, or just to karmically cleanse the intellectual property, the series seems to have stepped back from the abyss somewhat. There are still deadly and dangerous moments, but a leavening dose of lighthearted stories and what I will charitably describe as "zaniness" has been liberally added. Think of it as a generous dollop of cream to lighten up what was very dark and bitter coffee.

Being one of the old heads as WC readers go, I'm not sure how much I like it. Maybe I'm just the sucker at the table being separated from my hard-earned money with each new hand dealt or rather, book published. Except for Low Chicago, the "American Trilogy" books were mostly disappointing. See my review of Texas Hold 'Em here. Joker Moon (review here) was a step back in the right direction, but like a man who has had too much to drink, the series weaves and wanders, first one way then the next.

Which brings us to House Rules, the third book in the "British Trilogy" (or triad as the writers seem to prefer calling them). Knaves Over Queens returned to the earliest days of the virus and how it first changed the world, but this time from the POV of characters "across the pond". In many ways it was a return to greatness. Three Kings followed up on that promising reboot and built upon it. Then came House Rules.

House Rules

The premise of House Rules was loaded with potential. Off the coast of Cornwall is the mysterious island of Keun, steeped in ancient history and brooding menace. The enigmatic and wealthy Lord Jago Branok is using his seemingly limitless wealth to restore Loveday House, an ancient manor built upon the foundations of an ancient castle atop the cliffs of Keun. But neither Lord Jago or Loveday House are what they seem.

Jago is a wild card and often goes about masked and cloaked, leaving no one quite sure if he is an ace or a joker. Loveday House itself is-- strange. A place where the walls between worlds are thin, Loveday acts as a gateway between worlds, places where history turned a different corner; worlds where the virus never altered Earth's history, worlds where this or that revolution succeeded or failed, even alien worlds with strange skies and rulers that are not remotely human. With that in mind, I had thought that Loveday might provide brief glimpses into other worlds where WC history played out differently; a world where the Swarm conquered earth and absorbed aces into his genetic catalogue, a world where the Shadow Fists ruled New York instead of falling apart with the deaths or arrests of its most prominent members, and so on. It was not to be.

Instead, Lord Jago loves throwing parties and, wise or unwise, holds several a year. Jago repeatedly brings a variety of guests to Loveday with only some very flimsy warnings about the potential danger they might face. The guest lists range from lowly jokers and deuces (aces with weak or useless powers) to members of the Silver Helix (Britain's official ace superheroes). Of course, his guests are inevitably lured by visions of other worlds into parts of Loveday House where it is dangerous to go. After all, it wouldn't be much of a story if there wasn't any danger. The problem with House Rules isn't the concept, it is the execution. Something in the way this one was put together kept it from becoming more than the sum of its parts.

Wild Card novels come in a few different forms, most often an anthology collection of stories that all contribute to an overall narrative or the more ambitious and harder to pull off "braided narrative" or "mosaic novel" where the individual authors' contributions are edited together into one hopefully seamless work. The pattern usually seems to be two anthologies and a mosaic novel to wrap up the triad, but Three Kings was already a mosaic piece and House Rules bills itself on the cover as "a novel in stories", which is really what most of the WC anthologies are anyway.

House Rules would have worked much better as a mosaic novel. A friend told me it was originally planned as such, which makes much more sense than what we were given. The primary issue is with the individual stories split up to occur at different times of the year, each new set of guests has to discover there is something weird about Loveday House. So, rather than setting up the strangeness of Loveday, the details of the numerous "guise dances", and the malevolent forces seeking to control the old manor just once and then getting on with the story, there is instead a certain repetitiveness to the beginning of each tale. The protagonist of each new story doesn't know what has already been beaten to death for the reader. It would have been quite the trick to interweave all of the different story threads together, but it could have been done and likely to better effect than the odd, redundant story structure of the printed House Rules.

Jago the Munchkin

The other thing that got old very quickly was how Lord Jago, for lack of a better word, love bombs every single guest. It isn't just the strangeness of Loveday House we have to hear about over and over. Over and over we have to hear about how Jago spoils each guest with individually decorated, lavishly themed rooms overloaded with everything they could possibly want. It isn't just that the room is decorated in their favorite color or that the knocker on the door looks like their favorite animal. Indeed, those are just generalizations.

Jago stocks the bookshelves with their favorite books, the liquor cabinets with their favorite alcohol, the pictures in the frames are actual pictures of them or their favorite places or long lost family members and so on-- and on and on, ad nauseum. Rather than creating intrigue, Jago ends up seeming less like a host with infinite resources, though the text is at great pains to point out precisely that, and more like a demented stalker. Like Jago's guests, the readers are not tantalized but love bombed. The entire interwoven premise of Jago as a character and Loveday as a location tries way too hard to be cool. Instead of an embarrassment of riches it just becomes embarrassing, especially Jago.

Jago is not just yet another immortal Wild Carder from the very first days of the virus. Lord Jago is also vastly wealthy and a lord and super mysterious and has all sorts of cool weapons from other dimensions and has hordes of devoted servants who think he's great and knows everything about everything and has cool regenerative healing powers that keep him from being killed. In the old days of RPGs, be they player characters or the DM's pet NPC, guys like Lord Jago used to be called munchkins, a diminutive name for someone who just had to be the roughest toughest man of mystery with the coolest magic weapons and infinite hit points.

The Stories

The second half of the book is better than the first, which is damning with faint praise, I suppose. Shouldn't all books end more strongly than they begin?

Stephen Leigh, whose writing for this series I have previously enjoyed, turns in a weak set of interstitials featuring Gary Bushorn. Disappointingly, Bushorn's latest appearance undercuts to the point of nearly ruining that character's genuinely poignant tale in Deuces Down. After his visit to Loveday early on in the book, Bushorn becomes fascinated with the possibility the old manor might reunite him with his dead loved ones. He accepts an offer of employment from Lord Jago, who (for reasons of plot convenience perhaps) assigns Gary the role of dancing master. When Bushorn points out he doesn't know the first thing about the traditional "guise dancing" Jago is strangely obsessed with, the masked ace handwaves the issue away, telling Gary he'll be "a natural". Really, Stephen? The only black character in the entire book will be a natural at dancing?

Mary Anne Mohanraj delivers a cute little comedy of manners featuring a new character with a minor, but important power. With each new story Mohanraj writes she continues to build her own little corner of the WC universe, populated with her own intriguing take on aces and jokers. While ultimately inconsequential to the ultimate outcome of this "novel in stories" and partaking in the more recent whimsy that has crept into the series, Mohanraj's addition to House Rules was a brisk, enjoyable read that I found myself enjoying far more than I had thought I would.

Caroline Spector turns in a pasable murder mystery that ends the game for a long-running, though far from heavy-hitting character. Oddly, Spector's British protagonist, Constance, hates things that are twee, but the author's cozy little whodunit is pretty twee itself. Maybe that was by design. On a sidenote, is it just me or does Constance's dear departed best friend, a joker with flowers for hair, and her new ward, a joker with paintbrushes for hair, reveal a certain lack of creativity? The virus can cause any manner of physical mutations an author likes, but if a female joker hangs out with Constance, they just have weird hair.

Kevin Andrew Murphy's story indulges his own worst impulses as an author. Once you realize his protagonist is basically Murphy, the inevitable overload of decorative, architectural, folklore, historical flourishes and the provenances thereof (in a book already groaning under the weight of such stuff) really kicks into overdrive. At least he brought back Herne the Huntsman, threw in a gratuitous sex scene (those seems to have gotten ever more rare as the series progresses), and had the decency to make his self-insert character commit suicide. Murphy is not the only author in this collection that needs to remember mini history lessons and elaborate descriptions of architecture and paintings do not magically create atmosphere in and of themselves, but he is the one to do this the most in stories outside of House Rules. With luck, I'll never have to read about know it all antiquarian Nigel Walmsley ever again.

The last story is the best, which isn't surprising. Written by Peadar O Guilin, creator of the unforgettable villainess Badb from Three Kings, the final tale is a slam bang finish full of lowlife British aces and jokers out to steal whatever they can from Loveday House. Featuring an entertainingly sociopathic crimelord with the improbable name of Charles the Unkillable and a cameo by aged werewolf Mick Jagger, O Guilin's story lays the groundwork for a potential future menace in the form of a frightened woman under Charles's thumb. Her ace making her too valuable for Charles to give up and too dangerous for Lord Jago to ever let walk free, Maria is the only character to not seem overly impressed with Jago's cave of wonders-- and she negotiates her way out of his custody in practical but chilling fashion.

The final interstitial by Leigh, and Gary Bushorn's final fate, is unsatisfying. I won't spoil Bushorn's ultimate fate, but I will go on record with another small but significant grievance. Jago's letter to Bushorn reveals his (or perhaps Leigh's) misunderstanding of how recessive heredity in relation to the virus actually works. Jago tells Bushorn any child he might father with an uninfected woman has a fifty-fifty chance of having the virus. This is incorrect. Since the earliest books, it was established that both parents have to carry the virus for it to possibly manifest in a child.

Many happy returns?

As for the ultimate survival of Loveday House, I suppose the various authors are still too excited by the potential it represents to let Gary succeed in destroying it, but with the unrealized potential of this first book featuring Loveday I'm not sure a second hand will play out any better.

Comments